Research brief: Astronaut mice reproduce successfully

Every year, Genes in Space receives dozens of applications that focus on reproduction in space. And it's no wonder this issue has captured your imaginations: if humans ever expect to establish extraplanetary settlements, reproducing in space is one of the primary things we'll need to figure out.

2019 Finalist Vivian Yee

2019 Finalist Vivian Yee

What does the cutting edge of space reproduction research look like? To find out, we asked 2019 Finalist Vivian Yee. Vivian knows this field better than anyone; to prepare her proposal on gamete production in space, Vivian needed to read countless research articles on the topic.

Here, she shares her thoughts on one of the most exciting space reproduction papers to come out this year: an investigation by Takafumi Matsumura and colleagues that asked whether male mice housed on the ISS can produce healthy offspring.

Guest post from 2019 Finalist Vivian Yee

What was the purpose of this study?

Given recent interest in sending humans on long-duration space missions to Mars and beyond, scientists want to understand how the space environment would affect our ability to reproduce. Previous studies have suggested that it may be challenging to reproduce in space: space stimuli such as UV radiation and microgravity cause genetic damage to sperm cells and lower sperm counts. But no one really knows whether mammals can successfully reproduce in space. This study took a step in the direction of answering that question.

What exactly did the researchers do?

To complete this experiment, scientists flew two groups of mice to the ISS. One group was exposed to microgravity while the other was exposed to artificial gravity through centrifugation. Creating artificial gravity aboard the ISS is a neat technique that allows researchers to separate the influence of microgravity from other space stimuli like cosmic radiation and the forces associated with launching and landing. Both groups of ISS-housed mice were compared to a control group housed on Earth (a so-called “ground control” group).

After 35 days, both groups of ISS-housed mice were sent back to Earth, where scientists collected their testes and other parts of their reproductive tracts. The researchers looked at gene expression in the collected tissues and used a microscope to look for cellular changes. Sperm function was also assessed, both by measuring sperm motility and tail length and by impregnating female mice through in vitro fertilization. This allowed researchers to test whether gametes from space-housed mice could produce healthy offspring.

What did the researchers find?

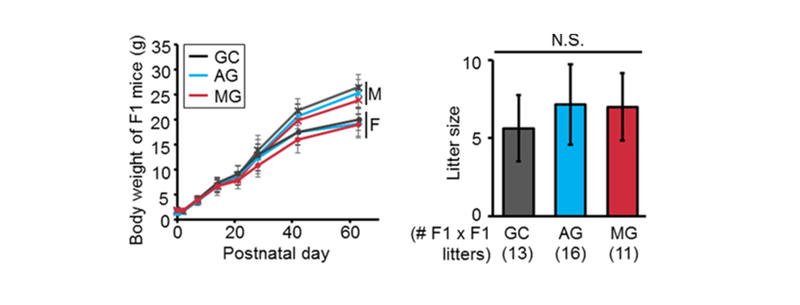

The title of this paper says it all: male mice sired healthy offspring after spending time in space. The embryos fathered by mice housed in microgravity and artificial gravity showed developmental patterns comparable to those seen in ground control mice. It seems the space environment does not have a significant, lasting impact on male reproductive capabilities upon return to Earth.

Left: Figure 3F from Matsumura et al. Growth curve of offspring produced from eggs fertilized with sperm from ground control (GC), artificial gravity (AG) and microgravity (MG) mice. Note that the body weights of both male (M) and female (F) offspring are comparable regardless of where the father was housed. Right: Figure 3G from Matsumura et al. Sizes of litters born to the offspring of space-reared mice. Note that the litter sizes between all groups are relatively comparable regardless of whether parents were sired by males housed in artificial gravity, microgravity, or on Earth.

This study further revealed that male reproductive organs undergo only small changes in response to microgravity. Differences in reproductive gland weight between the three groups of mice were minimal, and physical features and gene expression in male reproductive organs among ISS-housed mice were normal. Space exposure was seen to have a slight impact on sperm motility, but males were able to produce healthy offspring nevertheless.

What's next?

These results indicate that the space environment does not interfere with reproductive capabilities once an organism returns to Earth. However, it opens up the question of whether reproductive organs will function properly in space and if successful reproduction may occur in space. Further exploring mouse reproduction aboard the ISS may provide information about whether the human race might be able to sustain growth over many generations in space.

Moreover, this experiment ushered in the use of new apparatuses that allow scientists to use centrifugation to expose mice to artificial gravity while on the ISS. Going forward, tools like this will allow researchers to simulate partial gravity and allow for the use of “space-based control groups” for microgravity-related studies.

Inspired by this research? Have your own idea for a follow-up study? Submit it to Genes in Space! Application deadline: April 17, 2020.